Devina Dutt looks at the trend of unconventional performances in unconventional venues through Jyoti Dogra’s experience.

The day Notes on Chai , a striking monologue from Mumbai-based theatre actor and director Jyoti Dogra, opened at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Baroda’s MS University in August 2013, a freak storm visited the city. Only a few people could watch Dogra’s collection of stories, explicit and exact, held together by the everyday business of drinking tea. But the next day, a large crowd showed up in a bare classroom for a previously arranged Q&A session and Dogra decided to have another show, “without lights and the madness of bad mikes”, she says. The show and the conversations that followed were a revelation. Many in the audience had succumbed to the confessional tone of her stories and shared their own. “That led me to believe that the piece actually begins its real work post the show,” says Dogra.

That set the tone for the rich and disorderly way in which she has since found her audience; a journey as improvisational as her material in some ways. In the last two years, Notes on Chai has travelled through the country and abroad in places that are unconventional, sometimes even unusual. Many have been unplanned shows. But there have been unexpected rewards. Dogra says she has enjoyed pushing the performer-audience relationship out of the confines of mainstream spaces, especially because audiences at most regular spaces in cities like Mumbai — hollowed out by the relentless spate of “entertainers” — have become increasingly disengaged and uncomfortable with anything that seeks their involvement.

In smaller towns though, people tend to be more transparent. In Patiala, an overwrought professor confessed to her in Punjabi that he had not been able to breathe. Another woman, a former theatre actress forced to take up a routine academic job in Amritsar to please her husband, came back to tell her that she had gone back to acting after watching the show.

A show in Dharavi organised by SNEHA, an NGO that works with healthcare issues there, felt like an occasion because the audience soaked it in with unwavering attention. “There was an uninhibited simplicity in the way the women in the audience identified with that feeling of suffocation that is an important part of the piece,” says Dogra.

Sometimes the quest for spaces has been a matter of pure serendipity. Last year, travelling to the U.S. to visit her sister, a chance meeting at the Met with an actor who had attended her workshop in Mumbai led to two shows at The Tank, an experimental space for 65 people at the Times Square in New York City.

Dogra says that a recent unplanned performance in Thiruvananthapuram is one she particularly treasures. After performing at the Ekaharya festival in Kochi, she had called a friend who worked at Abhinaya theatre group in Thiruvananthapuram. As word spread, groups cancelled rehearsals for the day. An actor pitched in with lights while another prepared small hand-outs at his printing press. “Before we knew it, there was a full fledged show without worrying about how to raise funds and publicise,” she says.

But these journeys were also born of compulsion. Performing untypical works in space-starved cities like Mumbai is difficult. But it is an unstated conventionalism on the part of venues, which narrows performance opportunities, particularly for artistes who are not necessarily looking to create market-friendly work.

Dogra has been supported by organisations like the Indian Foundation for the Arts (IFA) for years. She has a following on the festival circuit with 30 performances in India and abroad. Yet she was not able to get a show in her hometown Mumbai at either NCPA or Prithvi by herself. Last week she finally managed to get a show at NCPA’s Experimental Theatre when a friend booked the theatre under a private event category and had her perform to a near-full house. Till then she had only performed Notes on Chai at Sitara Studio, as part of Prakriti Foundation’s Park Festival, and previously at a friend’s drawing room in Colaba.

The emergence of Sitara Studio in the central Parel and Dadar region, the erstwhile home of cotton mills and Marathi theatre, is reason to celebrate. Sitara has a grungy, flexible space with two main floors, and a jamming room for music bands. A few months ago, five young contemporary dancers completed their residency with Gati, a Delhi-based arts initiative specialising in contemporary dance. Keen to show their new work in other cities, the dancers got down to organising their shows.

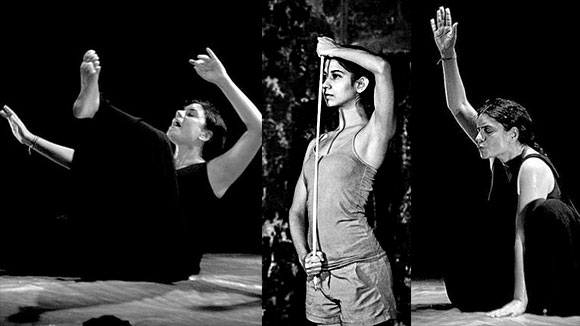

In Mumbai, low on funds and time, the only space that would host them was Sitara Studio. Riya Mandal, Rachnika Goyal, Venuri Perera, Avantika Bahl, and Mirra put together a well- attended mid-week show at Sitara, its warehouse ambience a perfect match for the varied performances as well as the conversation with the gutsy performers that followed. Says Nikhil Hemrajani, journalist turned arts entrepreneur, “We want to encourage independent artists from time to time.” The space was offered free to the dancers with all services and facilities with a sharing of ticket revenues to pay for running costs.

While in the U.S. last year, Dogra was in Washington D.C. when a friend who worked at the World Bank invited a group of friends from work for a show. Furniture was moved around to make space for 35 people. “After the show, we all ate and chatted about the piece, how differently each one related to this or that moment and it was a very beautiful afternoon. It was very personal and at the same time very public,” says Dogra.

But in India, where the arts are plagued by such fundamental shortages and forced to compete with the market logic of Big Entertainment, how can new work particularly of an experimental nature receive the support it needs? For that a more proactive idea of arts management first needs to take root.