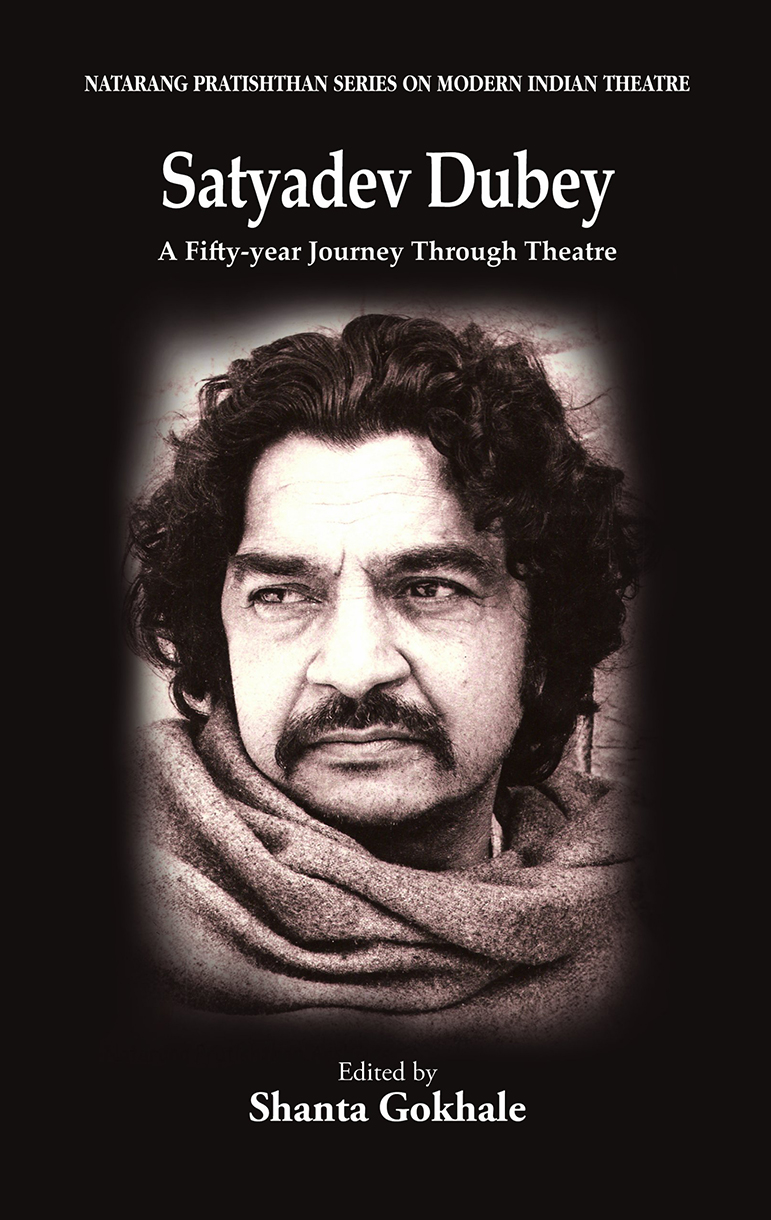

The myth of the maverick artist and the frisson of his conversations have often clouded the more substantive aspects of Satyadev Dubey's five decade long career as theatre actor, director and playwright. Satyadev Dubey, A Fifty-Year Journey Through Theatre, a comprehensive account of his work and influence on generations of theatre practitioners edited by writer and theatre critic Shanta Gokhale, sets things right.

Gokhale’s introduction describes the context of post-Independence theatre in India and goes on to trace Dubey's unique role in the propagation of plays from one region to another, capturing his naturally itinerant spirit wonderfully.

Discovering new plays, bringing playwrights together for readings and discussions, finding actors and new spaces and, crucially, knowing when to disband and move on, this is a detailed and intimate depiction of an important figure of modern Indian theatre whose influence exceeds even the fact that he directed 50 plays in 50 years in Hindi and Marathi as well as English and Gujarati.

One of the book’s achievements is the immediacy with which it collates a wealth of conversations, events and personalities from the world of theatre. As passionate and rigorous as its subject, the book is a rare piece of solid, yet accessible, and outward looking scholarship. Of particular significance is the manner in which a volatile Dubey and the city he migrated to mirror each other. Following the two narratives is to live through a closely observed history of the city of Mumbai, its politics and its changing character seen through its engagement with the arts.

Meticulous record

The portrait of Dubey and his work is meticulously recreated with translations and selections from an appropriately wide ranging set of resources including reviews, interviews, essays from magazines, independent journals and press articles in Marathi, Hindi and English. This unconventional approach offers readers the means to construct a more palpable and idiosyncratic cultural history of the last five decades.

Gokhale’s own interjections, which appear in the introductions to each piece, have a beautifully managed ebb and flow and range from analysis and cool objectivity to warmth and empathy. Remarkably, although they were friends, the book never descends into the insider driven hagiography common to this type of project.

Gokhale does a service to her subject by including the views of Delhi-based theatre practitioner and teacher Devendra Raj Ankur who faults Dubey for lacking newness and Marathi playwright Shafaat Khan's very personal and vivid account of the highs and lows of being intimately associated with Dubey. Dharamvir Bharati’s essay describes his first meeting with Dubey in the early 1960s. After a performance of “Waiting for Godot” directed by Alkazi with P.D. Shenoy, Alkazi and Dubey, he admires them for their “easy British accents” and is astonished by Dubey’s chaste Hindi when they meet after the show and the latter tells him he wants to discuss “Andha Yug” with him.

We go on to hear Shreeram Lagoo’s account of doing Tendulkar’s “Gidhade” and the firm letter Dubey wrote to the Stage Performance and Scrutiny Board. We find ourselves in the luminous half lit backspaces that exist in between languages and hear of his growing enchantment with the world of Marathi theatre. At one point Lagoo points out that, in the Marathi version of “Aadhe Adhure”, Dubey was able to catch the actors’ slightest mistakes, bringing alive the excitement of the complicated linguistic and cultural manoeuvres of that period.

Intense enjoyment

The book emphasises the man’s intense personal enjoyment of theatre and his refusal to intellectualise it, despite being very well read with the kind of passion for English literature that perhaps only English Departments in small towns can foster. “I have been obsessed by the search for a new idiom...the search for a new idiom is also a search for a new kind of theatre...” he was to say.

With an outsider’s instinct for opportunity, he was to mould himself into the character of his adopted city, making and unmaking himself every few years, learning new languages, finding friends changing his opinions as unfussily as an actor between acts unconcerned with consistency and commitment. He moved from an initial dislike for English language theatre to acting in and directing “Educating Rita” in the late 1980s, working hard on his diction to manage a sound that was correct, clean sounding English without being sterile or imitative.

The complex set of traits and beliefs that defined Dubey ranged from his unusual views on languages, poetry, the economics of theatre and his opposition to standard notions of modernity, theme and commitment in theatre. “It is my belief that when theatre is done as an institution fascism begins,” he said.

In its depiction of one individual’s passion for theatre, the book shows us why the arts are needed in every age and also suggests that there need not be an inevitable decline into hopelessness. As Dubey declares with absolute conviction and seriousness towards the end of a mock interview with himself, just two small theatres in Mumbai could do wonders for Marathi, Hindi and Gujarati theatre.