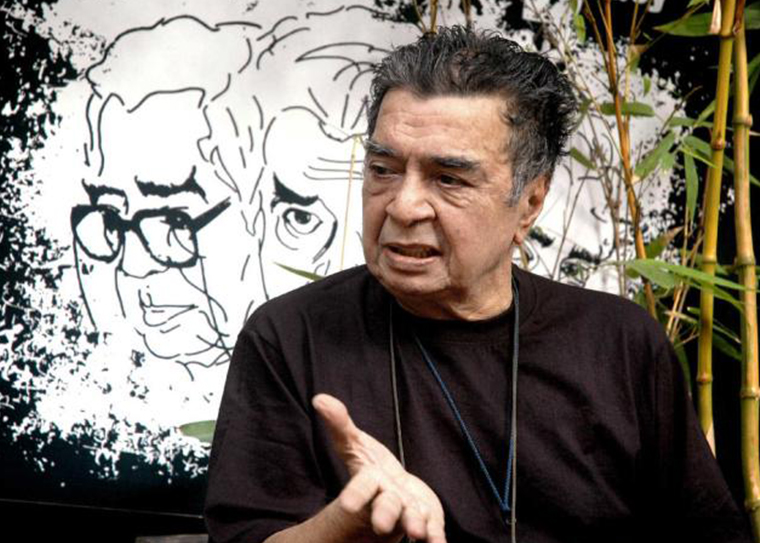

As the Prithvi Theatre Festival celebrates the work of Satyadev Dubey, the “most hated and most loved man of modern Hindi theatre” talks of his work and theatre in India.

“I’m not interested in adaptations of Dario Fo anymore though I will listen to an original play as I’m looking for personal perceptions ”

A day before the 30th Annual Theatre Festival at Prithvi Theatres is to begin, Satyadev Dubey is in his familiar environs at the open-air café. Banners proclaiming his status as the most “Hated and most loved man of modern Hindi theatre” are strewn across the Prithvi theatre grounds. At 72, Dubey is the theme of the Annual festival that comprises his handpicked plays.

His work over the last five decades as an actor, director, playwright and teacher is the subject of an evocative exhibition called “Theatre ke Anokhe Dubey” at Horniman Circle Gardens in the commercial heart of downtown Mumbai. It has been pieced together with the help freely rendered by generations of actors, playwrights, theatre groups and archivist from the worlds of Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati and English theatre crisscrossing the country.

Personal tribute

The festival began at Prithvi theatre in Juhu with a loving and personal tribute presented by old associates — director Sunil Shanbagh and actor Akash Khurana who guided the full house through the many quicksilver changes and highs of Dubey’s career.

Actors like Sulabha Deshpande, Ratna Pathak Shah, Utkarsh Mazumdar, actor and director Jaimini Pathak came on stage to reveal in moving and often hilarious ways why they loved the short-tempered and foul-mouthed Dubey and what he had done for their craft.

Dubey has insisted on focus, rehearsals, clarity in speech and repeated reading of text as well as figuring out if the scene in totality was “working” or not irrespective of other inputs and props. The three-hour show had tremendous archival value despite its informality and was a glimpse into the joy of doing theatre in Mumbai for the last five decades.

Arriving in Mumbai in 1955 from Bilaspur to become a cricketer, Dubey joined Theatre Unit, founded and run by Ibrahim Alkazi as an actor. Dubey is credited with discovering the theatrical potential of Dharmaveer Bharti’s “Andha Yug” which had been a radio play.

At the time Bharti had dropped in to see Camus’s “Cross Purposes”, which Dubey had adapted in Hindi as “Sapne”, locating the play in a remote Jammu village and bringing in shades of differently spoken Hindi and Urdu in keeping with the characters of the original play. “It was a credible adaptation,” he says.

His version of Sartre’s “No Exit” with Sulabha Deshpande and Alaknanda Samarth, which he had translated into Hindi and which performed at Tejpal auditorium for two back-to-back shows, was very popular. Characteristically he now says, “There were many hot scenes in the play. It must have titillated the audience”.

Today of course there is no interest in adaptations. “I’m not interested in adaptations of Dario Fo anymore though I will listen to an original play as I’m looking for personal perceptions now”, he says.

He debunks the idea of a golden age of Hindi theatre. “It was all accidental and full of coincidences. We were all young and discovering each other’s languages and cultures in a newly independent country. And for some time there was a lot of excitement and some good theatre was done but then by the early 1970s it had begun to fade due to the economics of the thing and other reasons,” he says.

By then a great deal of good work had been done. Dubey himself had directed and acted in several productions including Badal Sarcar’s “Pagla Ghoda” and “Evam Indrajit” in Hindi, Girish Karnad’s “Hayavdana”, Mohan Rakesh’s “Aadhe Adhure” and Vijay Tendulkars “Baby” to name a few.

In all these years the need to react and seek reactions has persisted. “I do have an audience in mind but I don’t think in numbers. I have friends like Shyam Benegal, Girish Karnad, Akash Khurana, Govind Nihalini who have been watching my plays for a long time. Their reaction matters to me. I’m very paranoid. So I refuse to book dates till I’m satisfied with my play.”

Into the film world

At the moment, he is excited with the idea of finishing his film “Ram Naam Satya Hai”. The screenplay of the film dealing with the subject of death is ready and he is looking to raise the funds to begin shooting.

He would also like to direct Girish Karnad’s latest play “Wedding Album”. “You see I know Girish, his family and the fact that he was thinking of this play for four decades. I’m excited about telescoping all those perceptions into one play. I will distort the structure,” he promises.

Not one of those who predict the demise of theatre, Dubey insists without invoking the platitudes of art versus commerce that theatre will survive because it’s a real need and for no other reason. “Theatre needs idealism and a sense of enjoyment and it will take care of itself,” he maintains. At the café, he hopes to turn at least a few of those who congregate around him into lifelong “theatre addicts” and “writing addicts”.

The talk at the café is seamless and not only about theatre. This is the day Barack Obama has been elected President. He stops mid-sentence to say, “It’s a revolution”, before correcting himself, “not a big revolution but a mini revolution any way. People must have wanted change to turn up in such large numbers. You have to give the Americans credit for that,” he says.

Critical rigour and careful analysis is not something he sets store by insisting on a personal vision from the playwright and director and a personal felt response from audience and critics alike. His selection of plays is fiercely individualistic too.

Although reservations and scepticism regarding some of his choices persist, it is difficult to resist the compelling sincerity and generosity of his instinct for salvaging and working with the most slender of positives. Thus he insists that “Cotton 56, Polyester 84” from Arpana Theatre Group, a play set against the backdrop of Mumbai’s vanishing cotton mills, is packed with information on an unknown facet of the city. Despite the thin writing and indifferent characterisation, one is compelled to revisit the play with another viewing.

Similarly, he praises the frequently gaudy and common “All About Women” from Akvarious Productions for its simplicity. Other plays selected by him include aRanya’s lyrical “Shakkar Ke Paanch Daane” and a fine production of Aasakta’s “Tu”.

As Marathi playwright Mahesh Elkunchwar says, “In theatre I have never met anybody who is kinder than Dubey. He once told me that he hated me, in fact all playwrights, but he loved my work, every playwright’s work… I have not seen or heard him, not once, saying an unkind word about someone’s text.”

Solicitude for the word

Minutes before the platform performance where Marathi actor Gajanand Paranjape reads Kumsumagraj’s poetry, Dubey goes up on stage and asks the audience to “make an effort to reach the poems even if you don’t understand Marathi. This is not theatre. It won’t come to you so you must make that effort,” he says. His solicitude and tenderness with the fate of the written word before a faceless crowd in a dark auditorium is irresistible. Typically, the moment is fused with personal memories as he reveals how he has loved reading these poems aloud before conceding that the actor will do a much better job than him and merges into the darkness back stage.