The modest offices of the Kerala Sangeetha Nataka Akademi (KSNA) in Thrissur were the venue for the fifth edition of the eight-day-long International Theatre Festival of Kerala (ITFoK). In this unassuming town, the virtually abandoned idea of the state’s responsibility to culture, particularly to contemporary Indian theatre, has resurfaced in a significant way thanks to the ITFoK.

ITFoK and the welter of contentious issues thrown up by the end of the festival this year, hint at a diametrically different view of theatre. In a year when it is impossible to deny its decline its very failure has proved revelatory, opening up the debate on the many questions linked to funding for the arts. The ITFoK case offers a rare opportunity for reclaiming lost ground and reimagining the role of theatre in contemporary India.

If representation from several European countries and serpentine queues forming an hour before shows were the sole measure of success, ITFoK could be counted as a stupendous hit this year. But it was clear that the best efforts of the organising team had failed to paper over critical gaps. Principal among them was the absence of any subtitling and an over-programmed schedule with as many as four plays a day including workshops and interactions with directors and cast followed by seminars. Poorly moderated discussions and an unremarkable selection of plays only emphasised the absence of an artistic director.

It was the ITFOK festival of 2010 with its focus on contemporary Latin American theatre that gave the festival its reputation as a brilliantly curated and executed festival. The core included Chairman Mukesh and Ravunny C., secretary of the KSNA, along with the Culture Minister M.A. Baby, one of the founders of the festival in 2008 and Abhilash Pillai, director and teacher at NSD, Delhi, as the festival director. This was a rare occasion when the usual personality clashes that plague the government’s culture departments were set aside to work towards a shared goal. Says Baby, “We wanted to identify the qualitative interventions in world theatre and bring them to Kerala so that our theatre communities could benefit from experiments. We also wanted audiences here to develop a mentality for appreciating experimental theatre”.

“It was a one-of-a-kind programming unheard of in India,” says culture critic Sadanand Menon who was part of the curatorial team. “There was boldness and ambition in the vision, in deciding to bring down Latin American plays knowing fully well the difficulties and expenses.”

During the festival there was a sudden strike and a two-day official mourning for former Chief Minister K. Karunakaran. But the theatre community in Kerala, a responsive press, government and minister came together and made it a memorable festival, recalls Menon. The festival brought together 650 artistes for 29 performances with 11 international groups and nine each from Kerala and the rest of India, over 10 days.

Critic and writer Rustom Bharucha who was there for a seminar that year remembers, “It was a combination of cutting-edge professionalism, which matched the highest international standards, along with the down-to-earth informality of Thrissur’s cultural scene and use of local resources, which made it so striking.”

For instance, visitors were deeply appreciative of two temporary auditoriums, built with bamboo and other indigenous materials, for the sheer finesse of their design and functionality. “It was a rare case of the local incorporating the global,” Bharucha emphasises.

The budget was the highest for any ITFoK at Rs 1.53 crore and the expenditure eventually touched Rs 1.85 crore. The Kerala government gave Rs. 50 lakh, the Central Sangeet Natak Akademi and Ministry of Culture gave Rs.10. lakhs and Rs.15 lakhs respectively and the South Central Zone contributed too. Additional funds were sought from other central government bodies including the ICCR (Rs.15 lakhs) with Dr. Venu, secretary in the Department of Culture playing an important role.

Critical to its success was the fact that the ITFoK 2010 team made its own selection of plays by contacting theatre persons and groups in Latin America directly. Martin C. John, an actor and director, was then based in Chile and helped make contacts across Latin American countries.

Sudhanva Deshpande, actor and director at Jana Natya Manch, Delhi remembers that the team came across an excellent play from Cuba that had a brief scene of frontal nudity. Wondering if it might offend sensibilities, the team approached Baby. His response, particularly in the current context of the politics of competitive hurt sentiments, was quite remarkable. “He told us that if we were confident of the play’s artistic merits we should bring it and he would support us”, says Deshpande. The play was staged without any incident.

Theatre director Shankar Venkateswaran who was the technical director says, “Every play gave us a sense of what that society was going through and we could read our own themes in those.”

The festival spent roughly Rs.65 lakhs on international travel whereas this year it was only about Rs.10 lakhs. Clearly, being able to pay for the passage of international groups and their crew is the difference between a great festival and a mediocre one.

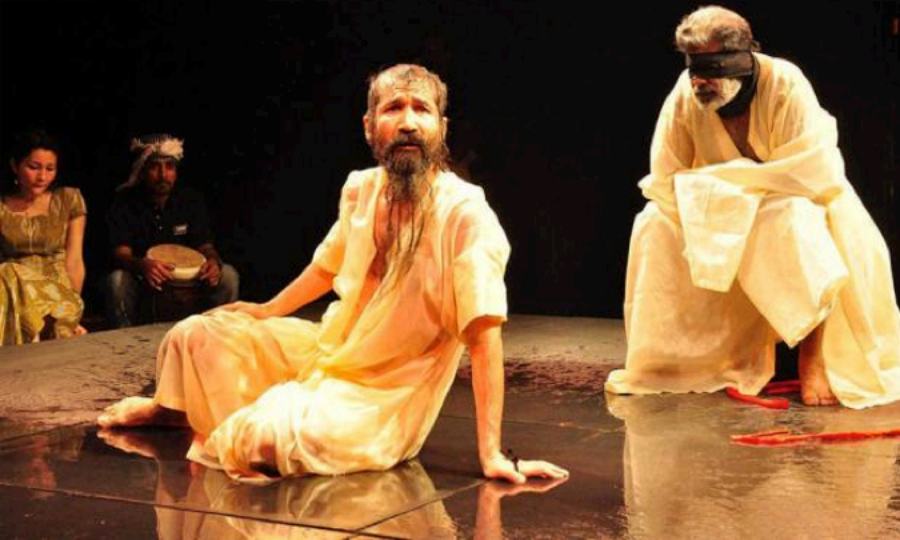

Maya Rao, theatre actor and teacher, whose Ravanama this year was one of the few highlights, was a spectator at the ITFoK 2010. “Everyone felt the difference in quality. It had to do with the fact that the theatre community was entrusted with the vision and execution. Theatre actors and groups are still reaping the rewards from connections made at that (2010) festival,” she says.

ITFoK 2013 is the first festival to have borne the full impact of the regime change after the Congress-led coalition, the UDF, came to office in 2011. Since the festival was organised without any assurance of funds, the organising team worked under extreme pressure and it was the international segment that was the most disappointing. Four weeks after it was over, Rs.50 lakhs was released against an expenditure of Rs 1.25 crore or so.

Soorya Krishnamoorthy, Chairman of the KSNA, who took over in August 2011 and appointed himself festival director, agrees that lack of funds from the government meant that “beggars cannot be choosers and we had to take whatever the embassies were giving us.” Indeed, Krishnamoorthy, a self-styled cultural impresario whose tastes often run to populist extravaganzas seems quite removed from the world of contemporary Indian theatre and its challenges. As head of the autonomous KSNA, it is his duty to seek government funding yet there is a persistent feeling of lack of seriousness and a sense that he is far too accommodating of the government’s reluctance to accord ITFoK the respect and funds it needs.

Proceeding to dub ITFoK 2010 as an example of wasteful spending, he insists that its expenditure was closer to Rs 2.5 crore and not Rs 1.85 crore. A simple check with his own office reveals that the expenditure was indeed Rs 1.85 crore. Next, he tries to explain away government inaction and lack of funds by blaming the media for its current obsession with film stars and cricket. “They are a democratic government and when they see it is not generating enough media interest they feel ‘what is the point?’”

Krishnamoorthy has also allowed the winners of various amateur and professional theatre competitions organised by the KSNA to be part of the ITFoK each year, uncaring that these plays could distort the curator’s vision and design. There is a shrewd attempt to categorise the ITFoK as a limited-appeal “elite” festival versus the populist and political gestures of offering health insurance and other benefits to registered artistes of the KSNA, but this is a false and mischievous divide.

He also tries to take credit for organising a festival cheaper than his predecessors. But is a frugal but badly curated festival with sub-standard plays a credit? For the next year, he says he has requested for Rs. 1 crore with the State Planning Board. Will that be enough when Rs.1.25 crore this year was not enough for a good festival? He has no answers.

ITFoK is clearly paying a cost for the regime change. When asked where the remaining amount will come from, Krishnamoorthy is vague and says they may have to divert funds from KSNA’s regular activities and also pass the hat around among friends including the patrons of his own organisation for help. Unmindful of how irregular this sounds he adds that his friends and private financiers including Malayalam superstars Mammooty and Mohanlal have contributed funds to the tune of Rs 25 to 50 lakhs towards the makeover of the black box and medical insurance for more than 5000 artistes registered with the KSNA. He speaks also of having an open air auditorium with “a see through glass top” and ACs for the black box for the festival next year.

The contrast between ITFoK and the International Film Festival of Kerala organised by the Chalachitra Akademi and supported by the Government of Kerala in Thiruvanathpuram for the last 17 years is quite stark. The film festival in December 2012 spent about Rs 3.70 crore. Perceived to be a prestigious event, budgetary proposals for it are always passed in the Assembly at the start of each financial year. The treatment given to ITFoK is a reflection of the poor status that serious contemporary theatre has in India. An international theatre festival that requires the transportation of sets, cast and crew, unlike a film festival, ought to deserve as much as the generous grant for the latter. In reality it does not even get half.

ITfoK’s annual scramble for funds will continue till it becomes a permanent activity of the KSNA. For this, the by-laws of the Akademi, in consultation with the Culture Department, need to be amended. Once this happens, every aspect of its functioning from selection norms to funding will be rigorously devised. This is the task that the previous government failed to do. Today, ex-minister Baby accepts that this has been a critical oversight.

In the theatre community, the fear is that the informal infusion of funds from “friends” could be used to set precedents for private sponsors and withdrawal of state support. Aware of the sharp criticism this year, Krishnamoorthy was quick to announce that an artistic director would head a 10-15 member Directorate in the coming year but, in the absence of assured institutionalised funding, what good would that do?

It is impossible not to sometimes view the five years of ITFoK as a face-off between a disorganised Congress-style philistinism on the one hand and a shrewd understanding of the power of culture with all its darker undertones that a Communist training allows for on the other. Ironically, in a democratic set-up in this case, so far it is the Left parties that have shown a better understanding of the aspirations of the theatre community and their audiences in Kerala as well as other parts of India. Will Indian politics ever be mature enough to carry a good idea forward and not overturn it just because it was given shape by an opposing party? Along with everything else, the ITFoK is a test case for that too.